The Great Purge (1933)

“If the dismissal of Jewish scientists means the annihilation of contemporary German science, then we shall do without science for a few years!” — Adolf Hilter

Prior to the 1930s, Germany had dominated the natural sciences for more than one hundred and fifty years. Its reputation for excellence in chemistry, physics, biology, medicine and mathematics was rivaled, if at all, only by Britan (Medawar & Pyke, 2000). Of the 100 Nobel Prizes awarded between the years of 1901 and 1932 (the year before Hitler came to power), 33 had been awarded to Germans and/or scientists working in Germany. For comparison, Brits and scientists in British universities had won 18 and the United States a mere six.

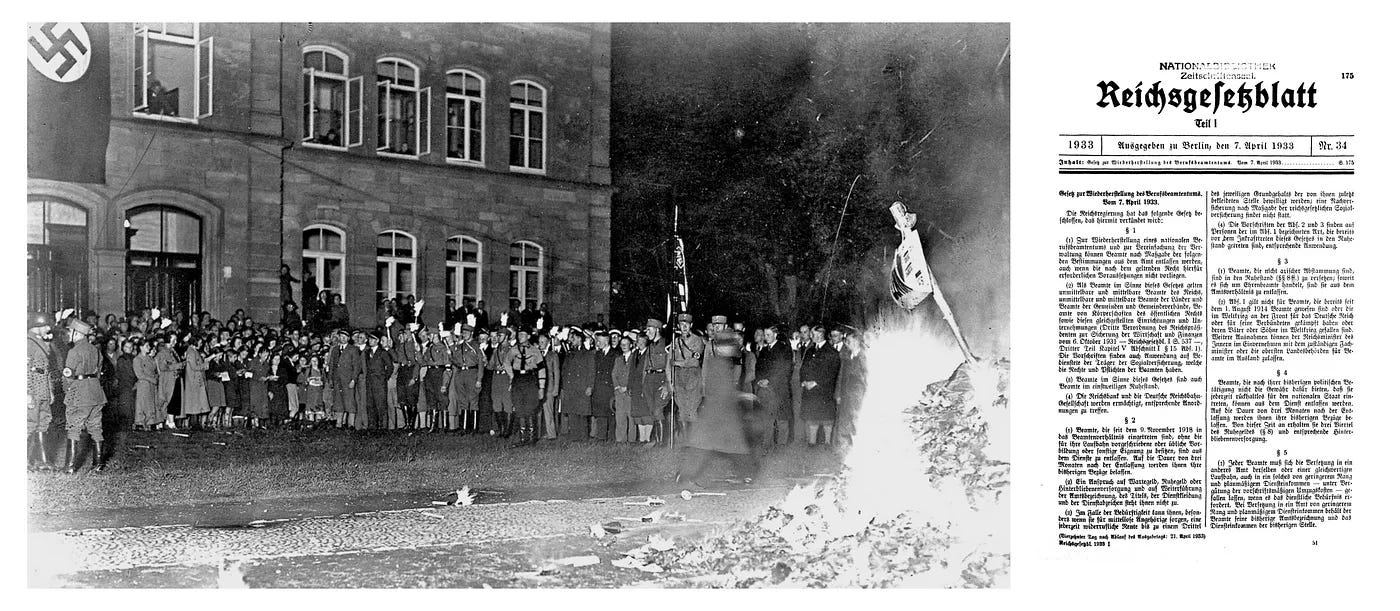

Then, starting in 1933 with the Nazi party’s seizure of control in Germany and their passing of the Berufsbeamtengesetz (“Law for the Restoration of the Professsional Civil Service”), certain groups of publ…