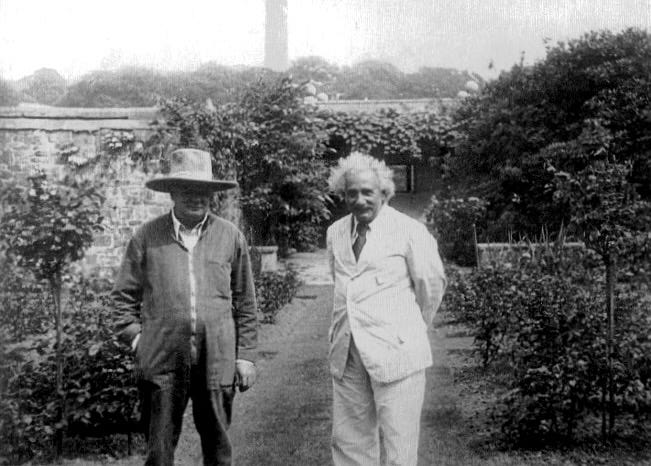

When Albert Einstein and his wife Elsa left Germany in December of 1932, Einstein for a period believed that he might be able to return one day, but he wasn’t certain. As late as December he wrote his friend Maurice Solovine (1875-1958) to “send copies” of his newly republished works “to me next April at my Caputh address”. Einstein and Elsa owned a weekend retreat in the town of Caputh outside of Potsdam. However, when they shortly thereafter closed their house up, Einstein is to have turned to his wife and said “Dreh dich um. Du siehst’s nie wieder”, which translates to “Turn around. You will never see it again” (Pais, 1982). Indeed, Einstein had in 1932 already been hired by Abraham Flexner (1866-1959) to take up one of the first six professorships at the newly founded Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey (see essay below)—alongside, among others, John von Neumann (1903-57).

On his voyage to America in 1933, E…